98 | A step-by-step introduction to the neurological system for veterinary nurses (ft Zoe Hatfield, RVN, VTS-Neurology)

Today I am super excited because I’m joined by a special guest, who is helping us understand one of the most complex systems of all - the nervous system.

I’m delighted to introduce Zoe Hatfield, a RVN and VTS in Neurology. Zoe is a RVN at Glasgow University Small Animal Hospital and also provides CPD on a wide range of neurology topics.

Over the next few weeks, Zoe will be taking us through some of the most common neurological diseases we see, giving us the need-to-know information to manage these patients confidently, and an insight into how we can use our skills to care for these patients as nurses and technicians.

But before we do that, we need to understand how the neurological system works - and as someone who still has to use the rhyme to remember the cranial nerves, I am really looking forward to listening to Zoe break this down for us!

So in today’s episode, we’re doing just that. You’ll leave feeling confident about how both the central and peripheral nervous systems work, and what happens to our patients when they don’t.

But before we do that, let’s talk about why understanding this is so important.

To successfully nurse neurology patients in practice it is vital that we understand neuroanatomy. Realising why changes to the anatomy can cause patients to display neurological deficits helps us as nurses to understand the nursing care they may require while they are hospitalised.

So what does the nervous system do?

The nervous system is vital for communication throughout the body. It is responsible for:

Receiving stimuli from the patient’s internal and external environment

Processing any stimuli it receives

And then initiating an appropriate response to the stimuli. This can be a conscious response, such as movement away from painful stimuli, or unconscious, such as secretion of saliva

The pathophysiology of the nervous system - and what it means for us as veterinary nurses

The nervous system can be broken down into the central and peripheral nervous systems, and the autonomic nervous system. The central nervous system (CNS) includes the brain and spinal cord. The peripheral nervous system (PNS) consists of the nerves located out with the brain and spinal cord.

The autonomic nervous system consists of efferent and afferent fibres that innervate smooth and cardiac muscle. This has both central and peripheral components. (the involuntary system for which you have no conscious control) and the somatic nervous system (the voluntary system, which is under conscious control). The autonomic system can be further broken down into sympathetic and parasympathetic systems.

The nervous system is made up of various operational units, including the nerves (and neurons), brain, meninges and cerebrospinal fluid or CSF.

Let’s start by looking at the nerves and neurons.

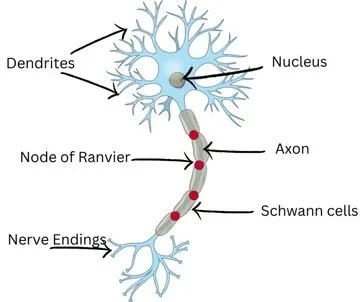

The nerves which communicate messages through the body are made up of smaller units known as neurons, which conduct electrical impulses. Neurons may be unipolar, bipolar or multipolar, depending on how many are joined together.

Each neuron consists of a cell body, axon and dendrites. Dendrites bring the information to the cell body and the axon transmits this information to other neurons or muscles.

Structure of a neuron. Source: Improve Veterinary Education

Neurons connect with each other to form an electrochemical circuit, which ensures electrical signals are transmitted correctly throughout the body systems.

Nerves are a collection of neurons bound together in cable-like bundles. Nerves are categorised as sensory (afferent), motor (efferent) or mixed.

Afferent nerves these receive stimuli from the external receptor and deliver them to the central nervous system.

Efferent nerves transmit the response from the central nervous system to the desired end location.

The transmission of stimuli occurs via certain receptors, which can be further categorised by the type of stimulus.

Special senses receptors which include photoreceptors, which respond to light, chemoreceptors which respond to odours and chemoreceptors which respond to taste.

Skin receptors include mechanoreceptors, which respond to touch, thermoreceptors which respond to heat, and nociceptors, which respond to pain.

There are also internal receptors involved in homeostasis. For example, baroreceptors respond to changes in blood pressure, while thermoreceptors respond to changes in core body temperature.

Next we have the central nervous system.

There are two types of tissue found within the central nervous system: grey matter and white matter.

Grey matter is involved in processing and integrating information.

It consists mainly of neuron cell bodies and their dendrites. In the brain, it forms the cortex (the surface) and deep nuclei. In the spinal cord the grey matter is centrally located.

White matter is responsible for transmitting signals between different grey matter regions within the brain and spinal cord.

White matter is composed mainly of myelinated axons, which is why it has a white appearance. White matter is found beneath the grey matter of the cortex and connects various areas of grey matter within the brain to each other. The white matter of the spinal cord is located externally and surrounds the centrally placed grey matter.

Then we have the brain.

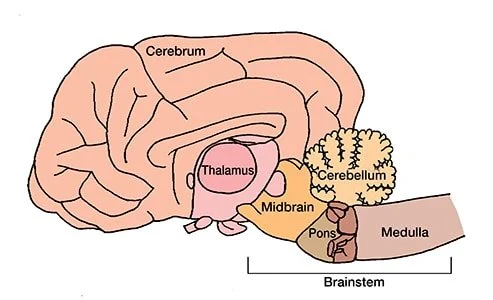

The brain is divided into three regions: the forebrain, midbrain and hindbrain.

The forebrain is made up of the cerebrum (telencephalon) and the diencephalon (thalamus).

The cerebrum is the largest part of the brain and is divided into two cerebral hemispheres connected by a mass of white matter known as the corpus callosum. Grey matter makes up the surface of each hemisphere, and the surface of these hemispheres are folded to increase the surface area (gyri).

The cerebrum acts as a reception for the taking in and processing of sensory input. It is also vital for information integration, voluntary motor control, memory and behaviour.

The diencephalon acts like a gateway between the brainstem and the cerebrum. Important structures relating to hormone production and regulation are found in the diencephalon region of the forebrain, namely the hypothalamus, thalamus and epithalamus.

These are responsible for autonomic and homeostatic regulatory control including salt/water balance, the circadian rhythm and autonomic responses to olfactory and emotional responses.

And this is the part of the brain I’m probably most interested in as an absolute endocrine nerd, because the hypothalamus controls a huge amount of hormone secretion, stimulating the pituitary gland to release various hormones, for example.

The midbrain (mesencephalon) is a relatively small portion of the brain, located in the rostral brainstem. It connects the forebrain with the hindbrain. The midbrain is involved in vision, hearing, motor control, sleep and wakefulness, alertness as well as temperature control.

The hindbrain is made up of the medulla oblongata, the pons and the cerebellum and it is located at the lower part of the brainstem. This area is crucial for regulating many factors important with the maintenance of life.

The medulla oblongata is responsible for cardiovascular functions, including regulating blood pressure and controlling heart rate and breathing. As well as managing reflexes such as swallowing, coughing, sneezing and salivation.

The pons provides a pathway for nerve fibres to relay sensory information between the cerebellum and cerebral cortex. Importantly the pons also houses the micturition centre, responsible for the control of urination.

The cerebellum’s general role is to interpret any movements in process or any movements being considered. It does so by receiving messages from muscles, the vestibular system and motor centres. While it does not initiate movements, the cerebellum feeds messages back in order to maintain control of fine motor movements.

As the brainstem is made up of the midbrain, the pons and medulla oblongata, these areas are usually collectively referred to as the brainstem rather than midbrain and hindbrain.

Cross-section of the brain. Source: Today’s Veterinary Practice

Moving out of the brain, we have the spinal cord.

The spinal cord reaches from the brainstem all the way through the centre of the spinal column, which is made up of the vertebrae, and finishes just before the end of the spinal column - this area is called the cauda equina, and is a sequence of thin nerves.

The spinal cord acts as a two-way highway, allowing the relay of sensory messages from the body to the brain and transmitting motor commands from the brain to the body.

It is also vital for controlling reflexes and autonomic functions such as bladder and bowel control. The spinal cord is divided into segments that align slightly cranial with the corresponding vertebrae.

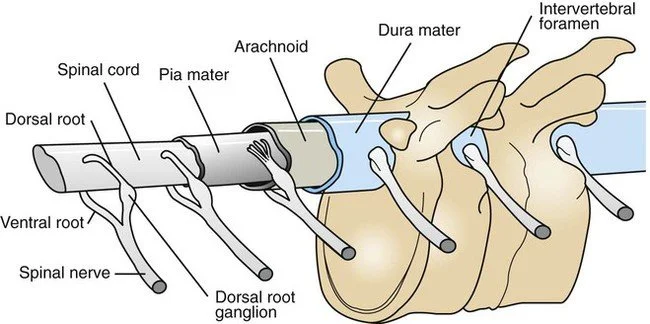

The brain and spinal cord are protected by the meninges.

Thinking about the brain and spinal cord, they are both delicate structures and require protection.

This comes in the form of the meninges – which is made up of three protective membranes (dura, arachnoid, pia mater) which cover the brain and spinal cord and house cerebrospinal fluid (CSF).

Spine, spinal cord and spinal nerves with meninges. Source: Veterian Key

And speaking of that CSF…

Cerebrospinal fluid is found in the brain and spinal cord. Its role is to cushion and protect these vital structures, and provide nutrients to the nervous tissues. The fluid is produced by the vascular plexuses housed in the ventricles of the brain.

So that’s the central nervous system, but what about the rest of the nervous system?

Let’s take a look at our peripheral nervous system (PNS).

The PNS connects the CNS to the limbs, body, head and the viscera. The PNS consists of the nerves and ganglia which are situated out with the brain and spinal cord. Comprising of the cranial nerves and spinal nerves, which extend from the spinal cord. The PNS is responsible for relaying communications from the brain and spinal cord to the rest of the body and vice versa. Signals are both sensory and motor. The PNS function is essential for normal sensory perception, muscle control and autonomic regulation. Dysfunction of the PNS can lead to sensory deficits, flaccid paralysis or decreased to absent spinal reflexes, as well as autonomic dysfunction (such as incontinence). These nerves are protected by Schwann cells; these myelinated cells give the nerves protection against injury. The Schwann cells collectively form the myelin sheath which surrounds the peripheral nerve axons.

When considering the PNS it is also important to remember the neuromuscular junction. The neuromuscular junction consists of an axon terminal, synaptic cleft and endplate and allows for electrical signals from the nerves to be transmitted to the muscles. One of the most common conditions caused by dysfunction at this area, is Myasthenia Gravis, and typically sees patients present with exercise intolerance.

There are a few specific nerves we also need to mention, starting with our cranial nerves.

The cranial nerves consist of 12 pairs of nerves that stem from the brain and control essential functions such as vision, eye movement, gag reflex and facial sensation. These nerves are a mixture of sensory and motor, with there being involvement from the autonomic and parasympathetic nervous systems.

For example, cranial nerve X (the Vagus nerve) is responsible for regulating several automatic bodily processes, including blood pressure, heart rate, breathing, mood, saliva production and more. It’s the main nerve of your parasympathetic nervous system.

And then there’s spinal nerves.

At every intervertebral junction, a pair of spinal nerves exit, one on the left and one on the right.

One side is the dorsal root, where sensory nerves enter the spinal cord, and the other is the ventral root, where motor nerves exit on the way to somatic muscles and visceral organs.

This structure means spinal nerves are mixed nerves as they contain both a sensory and a motor root.

Due to this combination, they can form a reflex arc, which allows a sensory message to travel via the spinal cord so a motor function is performed without involving the brain.

Some common reflex arcs include:

Pedal reflex – the pain receptors in the skin are stimulated, then the muscles of the limb flex to move the limb away

Anal reflex – another twitch reflex, this time in response to touch/stimulation of the perianal skin

Lastly, let’s take a look at the autonomic nervous system

Finally, It is important to consider the autonomic nervous system, which provides an unconscious motor innervation to most of the vital organs, such as the heart, intestines and bladder. It also acts on endocrine and exocrine glands.

The autonomic nervous system comprises two parts: the sympathetic nervous system, responsible for “fight, flight, fright” responses, and the parasympathetic nervous system, which generally opposes the sympathetic system.

This may seem a little confusing, so here is an example – the sympathetic effect on the bladder is to relax the bladder muscle and increase bladder sphincter tone, whereas the parasympathetic effect is to contract the bladder muscle and decrease sphincter tone.

The same goes for the eyes, as the sympathetic effect dilates the pupil, and parasympathetic effect constricts the pupil.

So we can use this information to look at the signs our patients are showing, help understand where in the nervous system the problem is (neurolocalisation) and then understand both the diagnostics and treatments our vets are likely to need, and the nursing we’re likely to perform.

And just like any other body system, understanding why these diseases happen and the impact they have on our patients starts with that thorough appreciation of how the system works, and what happens when it doesn’t. So Zoe and I (let’s be real - mostly Zoe!) will be showing you more of this over the next few weeks, as we dive into the common neurological conditions we see.

Thank you so much Zoe for joining us and teaching me and everyone else about how the neurological system works! Did you enjoy this episode? If so, I’d love to hear what you think. Take a screenshot and tag me on Instagram (@vetinternalmedicinenursing) so I can give you a shout-out and share it with a colleague who’d find it helpful!

Thanks for learning with me this week, and I’ll see you next time!

References and Further Reading

Thomson, C., Hahn, C., Johnson, C. & Roper, Q. 2012, Veterinary neuroanatomy: a clinical approach, Saunders Elsevier, Edinburgh.

Freeman, P.M. & Ives, E. 2020, A practical approach to neurology for the small animal practitioner, Wiley Blackwell, Hoboken, NJ.

Chrisman, C.L. 2002, Neurology for the small animal practitioner, Teton NewMedia, Jackson, Wyo

Platt, S.R. & Olby, N.J. 2014, BSAVA manual of canine and feline neurology, Fourth edn, British Small Animal Veterinary Association, Gloucester, [England]

Neurology – an anatomy refresher for veterinary nurses, Neurology – an anatomy refresher for veterinary nurses

About Zoe Hatfield, RVN, VTS(IM-Neurology)

Zoe qualified as a registered veterinary nurse in 2012. After spending her first year as a RVN working in first opinion practice, she moved to referral joining the University of Glasgow Small Animal Hospital nursing team in 2013.

Since joining the nursing team, Zoe has developed her passion for neurology and in 2019 gained the VTS certificate in Neurology.

Working within the vet school she enjoys using her extensive experience in neurology to teach and educate students and newer members of staff.

She also presents CPD on a wide variety of neurological topics, including at BSAVA Alba, ExcelCPD, VetTrust, AIMVT and BVA Live.

Watch Zoe’s excelCPD webinar series here.